Louis Harold Goodman

SelectRelation to Private ResetLouis Harold Goodman, the son of

Sam (Abram) Goodman (Rowinski), the son of Froim Boruch Efraim Rowinski, the son of Icek Josek? Abramowicz Rowinski, the father of Chava Sara Rowinska, the mother of Piah Yita Rowinska, the mother of Tobia Fajerstein, the parent of

Nomy Naomi Fajerstein, the mother of Private

- Parents: Sam (Abram) Goodman (Rowinski)Eva Beeth Rothberger

- Siblings: Sarah Goodman Kapelow

- Spouses: Margie Sylvia Evensky Goodman

- Children: Private and Private

- Gender: male

- Birthplace: Canton, Stark, Ohio

- Deathplace: Memphis, Tennessee

- Graduation date: 1937-01-27

- Occupation: Liquor store proprietor

- Occupation: Soldier in World War II

- Occupation: Lumbermill operator

- Occupation: Nursery supply wholesaler

- Occupation: Proprietor

- Occupation: sales

- Wedding date: 1943-01-31

Biography by Susan Katz

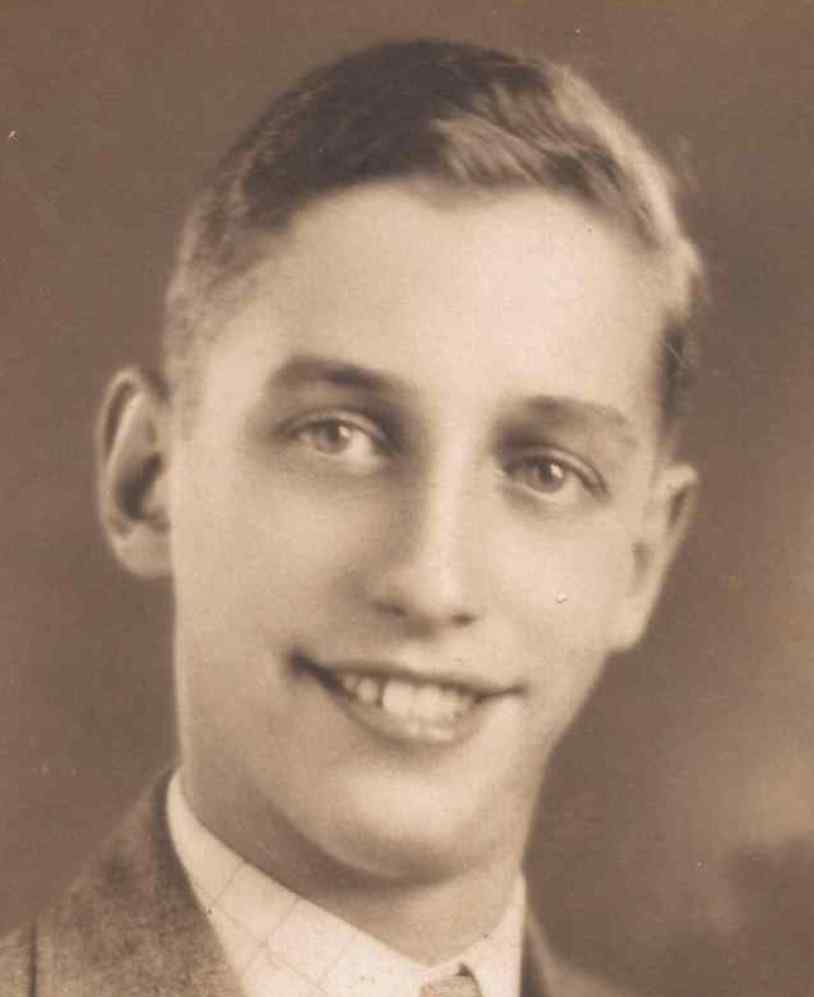

It's said that a man's soul lives on in the memories of his loved ones. I have many memories of my father.

My father had the biggest, most beautiful, clearest blue eyes I have ever seen. (Elysa, are you laughing at this line?)

When I was a little girl, I remember sitting on the couch in the small den of our home on Henry Street, listening to Daddy reading, once again, my favorite story, "The Runaway Polka Dots". He would then say, "Let's tiptoe through the tulips," before picking me up and carrying me, laughing, to my bedroom where he would throw me gently on the bed and tuck me in for the night.

Often, the monsters would wake me up in the middle of the night, and I would go crying into my parents' bedroom. Mother would say, "Lou, go lie down with Susan in her room," and he would wake up, without complaint, and stay with me until the monsters left, and I fell fast asleep.

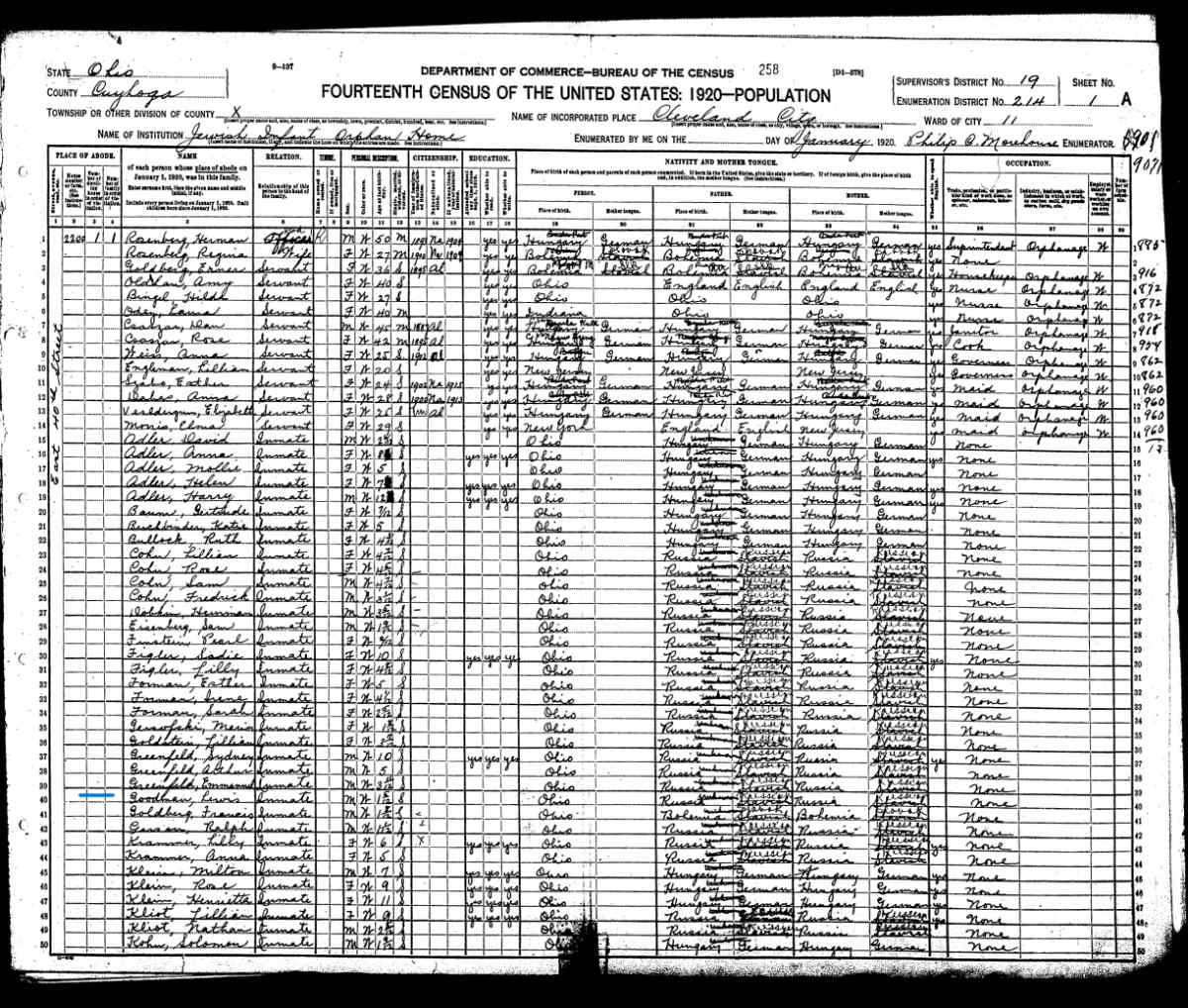

Census of the jewish orphanage where Louis was an "inmate" at 1 year old.

1920 Census record of Louis (Lewis) Goodman at the Cleveland Hebrew Orphans Home.

Louis H Goodman as a young man, maybe 5 or 6 years old

Later, he would do the same with my Byron and Elysa, but he embellished it a little for them. He would count their toes, constantly making mistakes, so that he would have to count them again and again.

Usually on warm-weather Sundays when I was a child, we looked forward to his delicious barbeque. He would start the charcoal in the brick barbeque pit which was some distance from the house. I was in charge of holding the bowl of barbeque sauce (he only used Maul's with Tabasco and Worcestershire thrown in, for good measure), and every now and then he would teach me the finer points of basting the kosher veal ribs or chicken. "It's time to turn them, Susan. Give them a good basting with the brush. Now, turn 'em again." Finally, the meat would be just perfect, crispy, and glistening with the many layers of sauce, and he would take his knife and cut off a small piece from the best part, cut that into two pieces, and each one of us would eat a "sample".

Sarah Goodman, Bertha Goodman, and Louis

A picture of Sarah Goodman, Bertha (Blema) Goodman, and Louis Goodman in the 1920s, sitting on a porch swing.

Louis Goodman's 1936 yearbook photo from Lorain Ohio

On these days, he would also hand cut French fries from huge Idaho potatoes. He would stand at the counter in the kitchen, and patiently peel, slice, turn, and slice the potatoes again so that the French fries would be wonderful for us. And they always were.

On Henry Street, my brother and I would often play in the "dollhouse" which Daddy built. I remember him hammering and nailing the boards together. It was situated in an area of the yard that was somewhat near the big climbing tree. I loved that dollhouse; it always seemed so mysterious and protective. It was a real house, with a roof and windows, nothing prefabricated. We placed chairs and bookcases in there so we could read.

closeup of Louis Goodman in yearbook, 1935

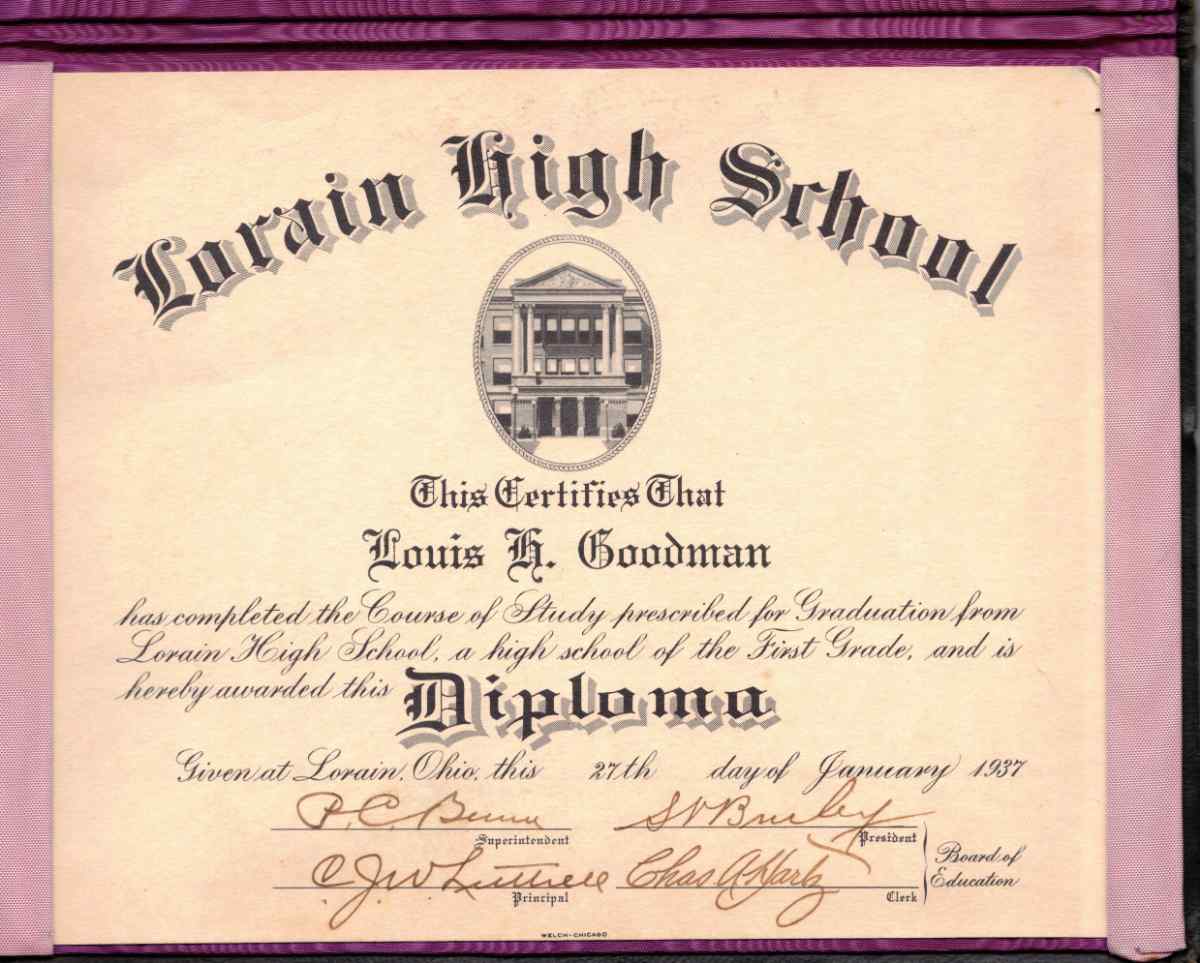

Louis Goodman's High School Diploma, 1937

From the Lorain High School, 1937, Lorain Ohio.

Daddy would throw a baseball back and forth with Gary every night after he came home from work. If he ever complained about it, I was never aware.

Fishing was Daddy's passion. He built a small, rustic cabin at Snow Lake, in Mississippi, where we went most weekends from the time I was in second grade. I remember when he first showed us the property. For each lot purchased, the developers were offering a discount of two hundred dollars or a Shetland pony. I couldn't wait to ride and play with the Pony! To this day, I've never seen one of these animals up close.

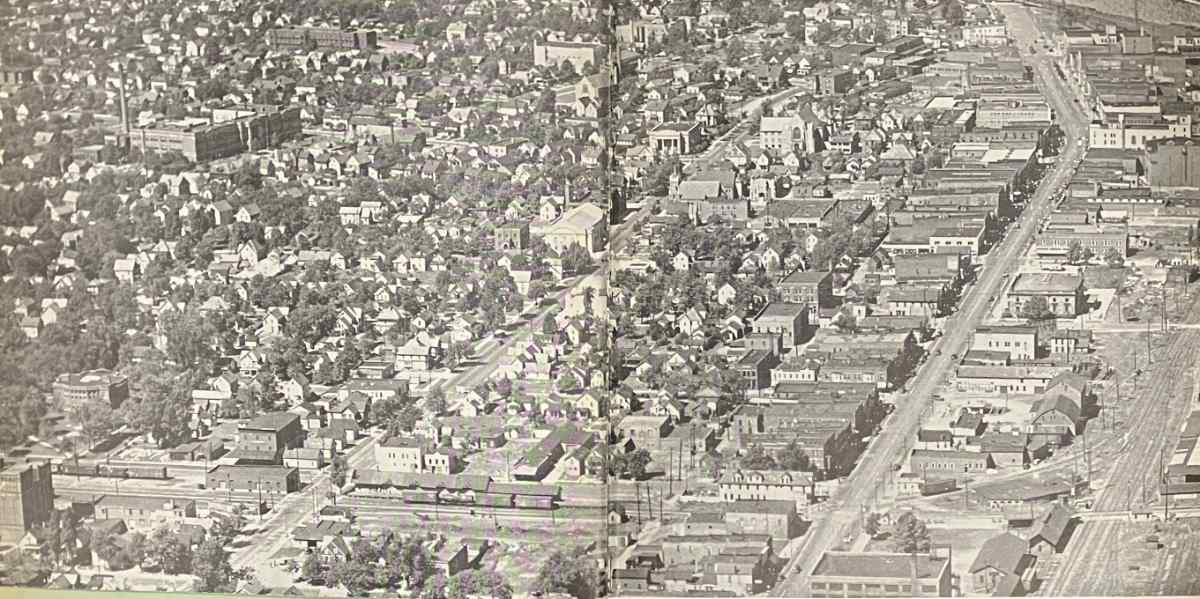

Lorain Ohio, 1935

Because my parents were Orthodox, my father couldn't use the fishing boat on Shabbos, and so, on that day, we would walk the mile to the man-made lake's sandy beach to go swimming, or we would read. But on Sunday, we would all climb into the boat and go "trolling", and catch delicious bass and brim. He would take us to the quiet, shady coves in the lake where the brim were, and we would wait patiently, without talking, so they wouldn't know that we were looking for them. Even though he usually used professionally-made lures, he would often stop on the way to Snow Lake to buy crickets or minnows. I still remember sitting on the pier with him while he gave me tips on how to hook a minnow. I don't think I would ever touch the crickets. When the fish were caught, we would putter back to our pier, and he would bring the line of fish into the house and throw the fish into the sink. Eventually, he scaled and cleaned these delicacies, and my mother would fry them. He always loved fried fish.

Grandma Margie Goodman, Grampa Louis Goodman, Susan Katz and Ron Katz at Byron and Susanne's wedding in Braselton, Georgia, Chateau Elan

For a few years, I had the chance to work with him. I gained an appreciation of the difficulties he and my mother had in persevering with their business. But he always maintained a sweet and caring disposition, even when I really screwed up. He would listen as I talked to customers, and ever so often he would give me advice in such a sweet way that I didn't realize until much later that I had so much to learn. "Less said, best said," took on an important meaning to me. Also, "If you only say the truth, you won't have to remember what you said." Daddy was a brilliant man; he was always reading The Wall Street Journal or some other publication. He was a sounding board for my problems, and his advice was only positive and loving.

portrait of Margie and Louis Goodman, with Louis in his army uniform

wedding of Margie Evensky and Louis Goodman,January 31, 1943

Bride: Margie Sylvia Evensky Groom: Louis Harold Goodman Bride's father: Julius L Evensky Matron of honor: Bessie Evensky Senior matron of honor: Goldie Margolin Maid of honor: LaVerne Evensky Bridesmaids: Sylvia Shankman, Rosemarie Romeo Groomsman: Sam Margolin, Nathan Evensky, Ben Margolin Ushers: Phil Evensky, Joe Margolin, Herbert Evensky, Ben Levitch Groom's Aunt: Mrs. Regina Fishhein Flower girls: Emily Sue Margolin, Marcia Faye Evensky Rabbi: Isadore Goodman Cantor: Rev. M I Levin

He was always slow and methodical, in everything. He would say, "One thing at a time." He would drive everyone crazy when he was at the wheel of his car. If he went faster than thirty miles an hour, he thought he was speeding. (His one and only "speeding" ticket was for driving too slowly.)

Once, when yet another irritated driver who was behind him on the road started honking his horn, my father calmly stated, "If he wanted to get there earlier, he should have left earlier." He never acknowledged that, just possibly, it was that he was driving too slowly. A number of years ago, I was driving somewhere from my home, late as usual, and kind of speeding. I turned right onto the main road and saw a major traffic jam. Obviously, there had been a bad accident. In one lane, cars were lined up as far as the eye could see, and I knew that I would never get wherever it was that I was going. Finally, I was able to pull over to the left lane and speed up around the line of cars. At the head of the line was my father.

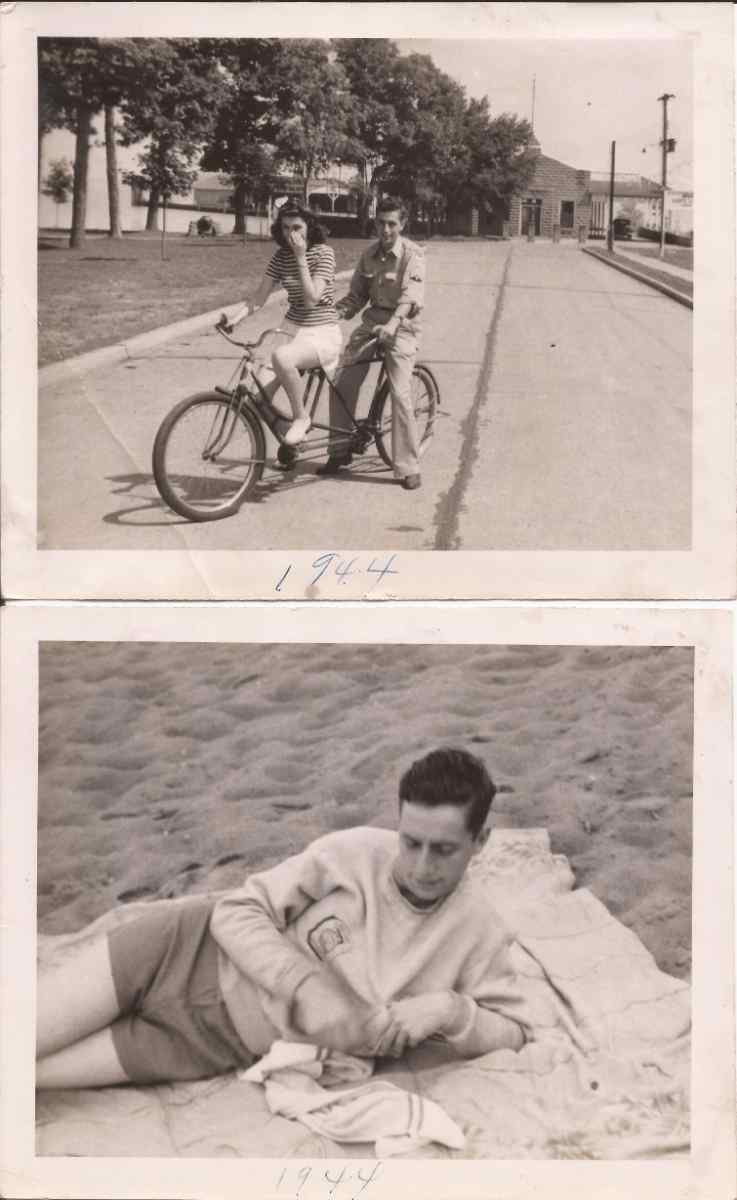

Louis and Margie on a vacation, 1944

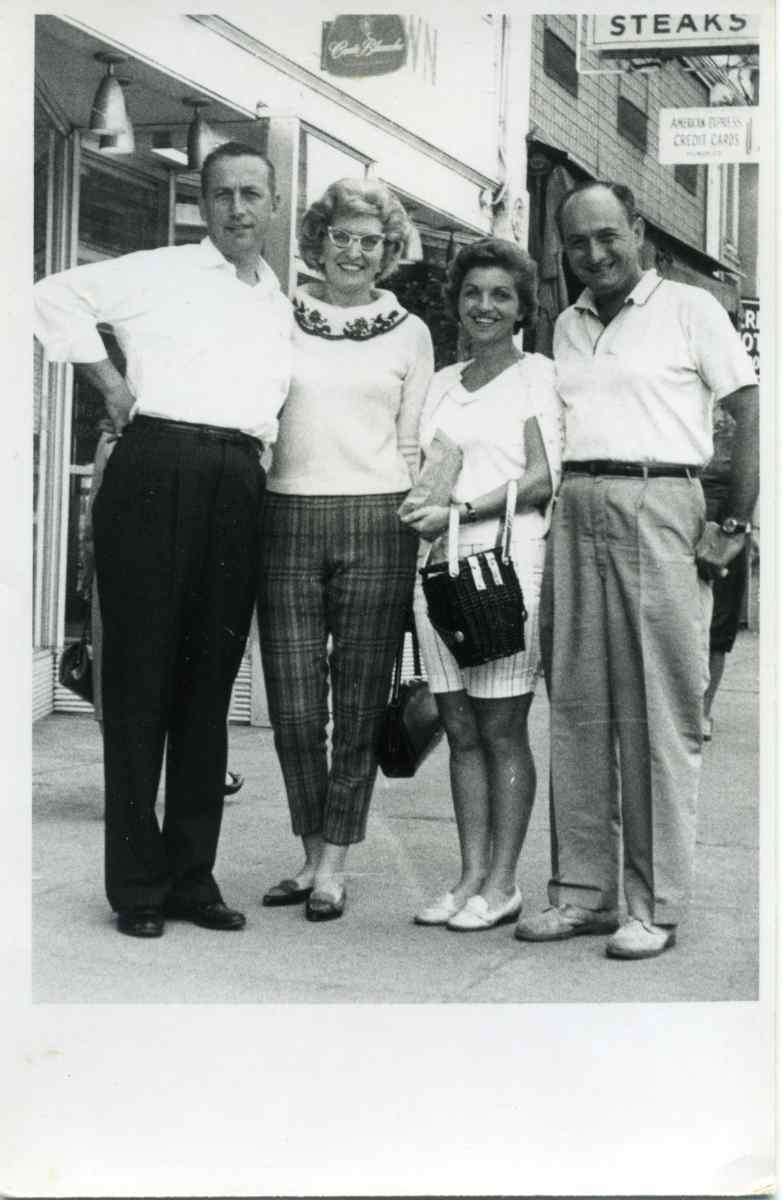

Alex Milaski, Sarah Kapelow, Louis Goodman, Saul Kapelow in the late 1940s.

In later years, my parents did well financially, and when my brother and I were in college, the family was able to travel. I remember one trip that we took to Europe when we visited a number of countries. My favorite was France. I had always loved the sound of the French language, and I was taking a number of courses at the university. Daddy was driving us through the countryside of France, and we were lost. (We were always getting lost or knocked off the road by truckers. There was the time that we were supposed to be driving to Oxford, England, and we ended up in the opposite direction at Cambridge. We all kept telling him that the road signs were saying Cambridge. Daddy's response was that he knew where he was going...Apparently, it was Cambridge.) Anyway, we were on a dirt road in France, and we were lost. There was a man and his university-age son working in the field in front of their country farmhouse, and Daddy pulled over to get directions. Mother turned to me and said, "Ask them in French where we are." Naturally, I froze. I was soooooooooo embarrassed to speak French in front of real French people. After we pulled away, Daddy muttered, "All that goddamn money I'm spending for college, and what good is it?"

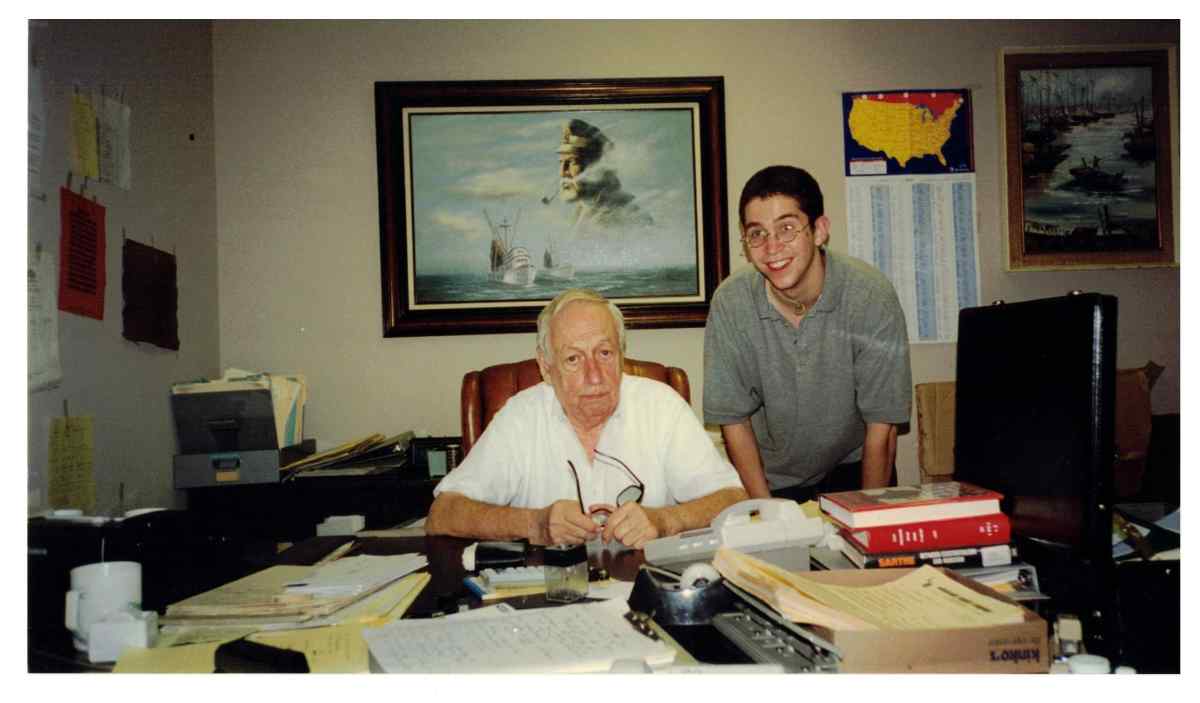

Louis H Goodman and his grandson, Byron Katz, at Byron's wedding. Chateau Elan, Braselton, Georgia, 2003

As he grew older, he insisted on maintaining his independence. He refused to accept help in the form of a caretaker. He himself was the caretaker of my mother, and that was that. The last time I had lunch with him, at his favorite restaurant, I insisted that he bring Theotis. The week before, while eating lunch with my parents, my father could not stand up and panicked, and many people in the restaurant had to help him with his walker. I was worried that he would get hurt the next time if someone were not there to help him. We had a serious talk as he and Mother were getting into their car to leave, and he promised that Theotis would be with him any time in the future when he left the house. Anyway, the next week when I was on the phone making plans to meet him that day at McDonald's, I reminded him about his promise.

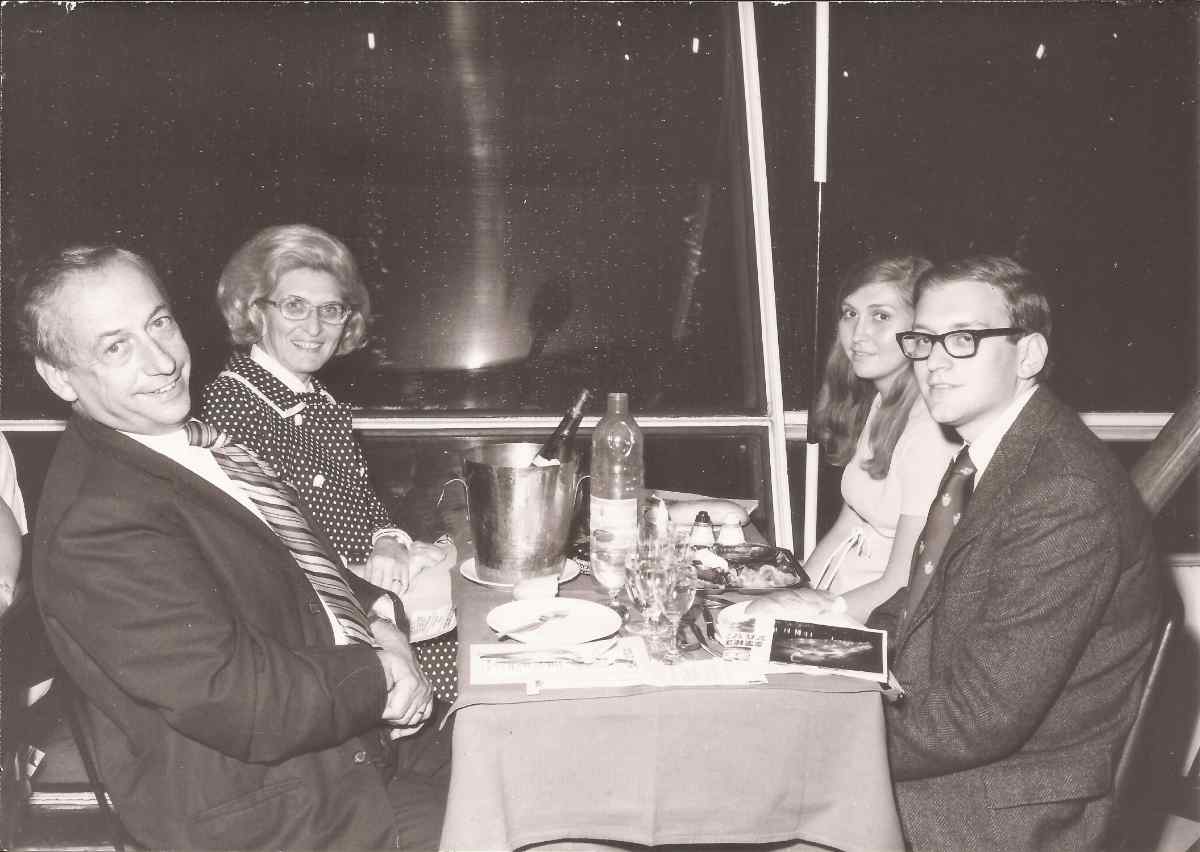

Louis Goodman, Margie Evensky Goodman, Susan Goodman Katz, Gary Goodman, having dinner

A formal dinner, with several in attendance

In attendance, from the left: Bessie Margolin, Julius Evensky, a young Gary Goodman, Margie Goodman, a young Susan Goodman Katz

Right before lunch, I drove to the bank to run an errand, and when I finished I looked out the window at McDonald's which was directly in front of the bank, to see if Daddy's SUV was parked there. Usually, we ordered our fish sandwiches at the drive-through and ate in the car so that he would not have to get out because of the great difficulty he had in walking.

I saw an SUV that looked familiar, but no one was in it, and I was expecting two people, Daddy and Theotis. So I waited a while, taking care of some business, until I thought that maybe his car was on the other side of the restaurant, where I could not see it. I walked across the parking lot, through the door, into McDonald's. There was Daddy, sitting all by himself, waiting so patiently for me to meet him for lunch. To this day I don't know how he maneuvered getting his walker out of the car by himself in order to manage the complicated feat of walking inside and sitting down. We had a good lunch and a better conversation. Until the very end, he had a sense of dignity.

Louis Margie Bette and Ken

photo-postcard, dated 10/26/1961. Louis and Margie Goodman, Bette and Ken Goodman, Hot Springs, AK.

One day, when Daddy was dying in the hospital, I was on the phone speaking with Elysa. I was bitterly complaining that life had been very unfair to him. At the beginning of his life, his mother died when he was just a few days old, and he was placed in an orphanage for a couple of years before his father (and the new wife, the wicked stepmother) reclaimed him. And now, his ending circumstances were cruel and inhumane. But she wisely commented that even though this might be true, the middle portion of his life, which, she said, was in a sense, his real life, was very good. He had a family that loved him, he was a successful businessman, he was able to afford any luxury he or his family wanted, he had many friends, and he had been honored by the shul and the members of his community. Life for him, as she explained, had been rewarding and full of joy.

Louis and Margie Goodman walking in Hot Springs, Arkansas, 1960

While in the hospital at the end, he still maintained his intellect. He wanted to see his two-year-old great-grandchild, but Daddy was in the hospital in ICU, and there was no way that it was possible. But he wouldn't be stopped. He concocted a plan in which Byron and Susanne would bring Cameron to his hospital window. No one else had thought of it. The next day, Ron and I entered the hospital room, and Ron played a video of Cameron on his cell-phone to show Daddy. As Daddy was intently watching the video, Byron, Susanne, and Cameron walked up to the window with smiles on their faces. While Daddy was looking at them, Ron turned off the video, and called Byron's cell-phone, so that Daddy could hear Cameron's voice.

Louis Goodman with his grandson, Byron Katz

At the funeral, the Baron Hirsch chapel was overflowing. In the sweltering heat of a Memphis July, family and friends who couldn't find seats were standing outside, listening to the Rabbi, who talked about Daddy's wood "cravings", and how he was like a tree with many branches. At the gravesite, Ron took a few moments to comment how Daddy had such a big heart and how he was so good to him and to all of us. Elysa told me her story of the time Dan stayed with my parents on one of his visits before they married. Each morning, Daddy would wake Dan up so that he could fix him what he considered to be a proper breakfast. I imagine he enjoyed Dan's company. During the week of shiva, so many people came to visit. Literally, over a hundred people visited, brought food, sent donations, or wrote beautiful messages in cards. Cousin Greg said, "I had to be there; he was my Uncle Lou-Lou"." Other cousins said, "Everyone loved your father." People my mother and I hadn't seen or talked to in years sent donations and condolences. One cute story that sticks in my mind is when Mr. Siegel, one of Daddy's oldest friends, came to visit during shiva.

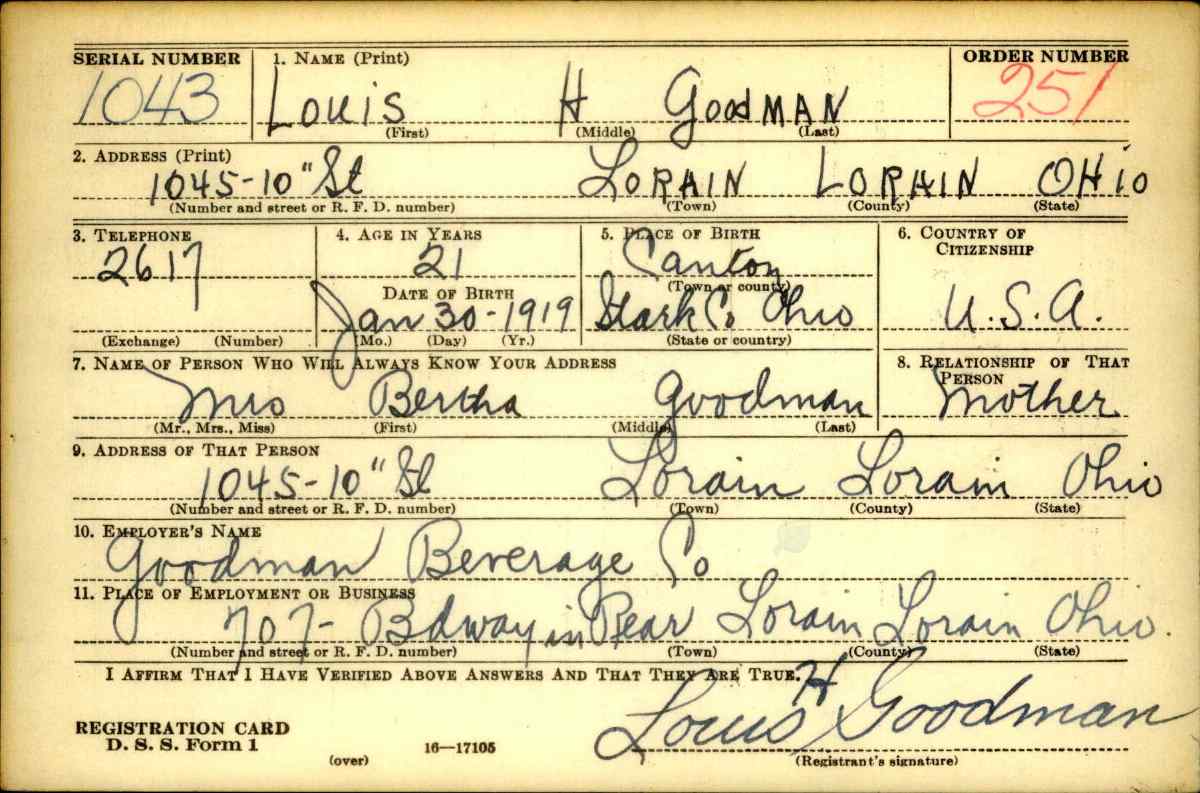

World War II draft card

Twenty odd years ago, Mother and Daddy built their current home, and at one of their many luncheon engagements then, Mr. Siegel asked Daddy, "Lou, why are you building a new home at your age?" My Siegel said that Daddy glanced up at the ceiling the way he did, looked back at Mr. Siegel and said with a straight face, "So Margie and I will have something to talk about."

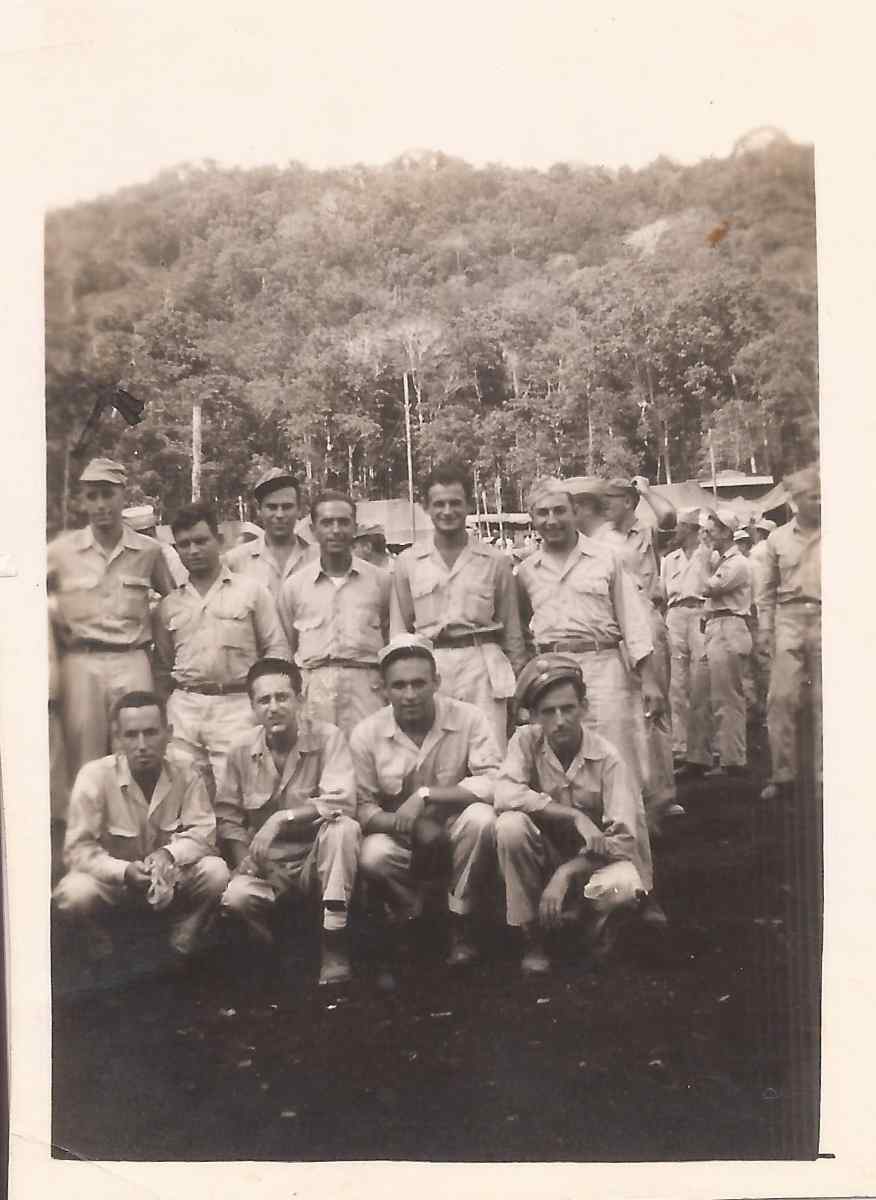

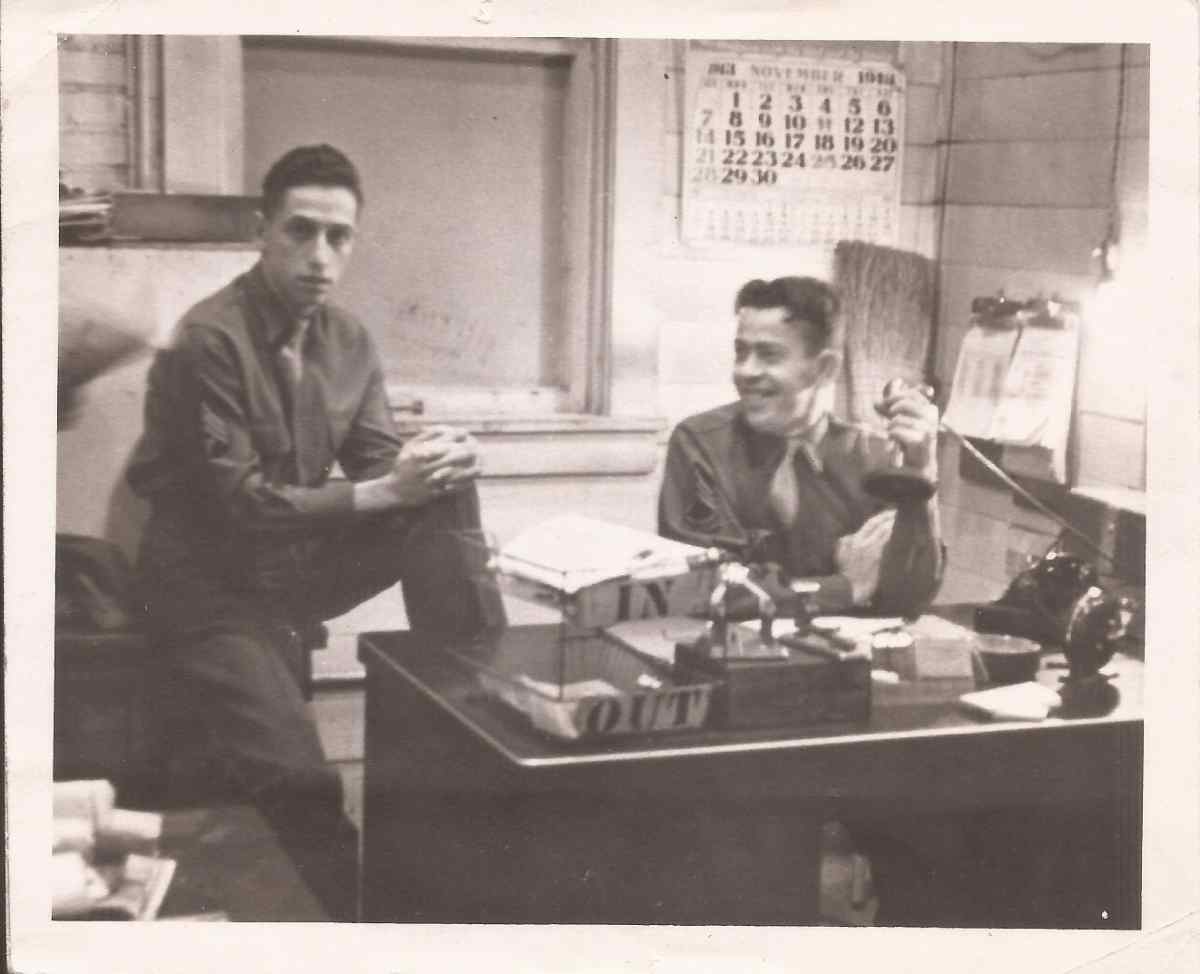

pictures from the army, taken by Louis Goodman

In the hospital, Daddy and I talked about a few things. He reminded me that his mother, a Rothberger, was from Hungary, and that he had been the first kid drafted from Loraine, Ohio, during World War II. During the war, he had received a bronze star, and he used to love to tell the story of it.

Louis with his fellow soldiers. Louis in top left.

As a young soldier, he had been stationed in the Philippines, on one of the islands. One day, knowing his men were bored (he was their sergeant, and he was probably bored, too), he decided that they could go exploring on another nearby island for souvenirs. They landed and scattered, looking for knives or other trinkets that the Japanese soldiers might have dropped there, before they had all left the area. He and his men were enjoying the day, when all of a sudden, they heard Japanese voices! Unknown to them, the island was not deserted, but still occupied. Running as fast as they could, they were thankful to make it back to home base where he reported the sighting. Subsequently, he received a bronze star for his bravery and foresight. He used to really make me laugh about this. The Japanese knives he collected are framed in a shadow box on his wall.

Louis in the army, standing at attention with his rifle.

To digress for a moment, let me mention K-Mart. Did I tell you that my father was frugal? Cheap was more like it, at least if he were buying something for himself. He would buy clothes at the cheapest place possible, and brag about it. He would compete with me to see who had the cheapest light bill each month. But if my mother, brother, or I wanted something, nothing was too expensive. His heart was very generous, and he wanted his children and grandchildren to feel secure. As long as it was for those he loved, anything was possible. He always reminded me, "As long as something can be replaced with money, you shouldn't worry about it."

Louis Goodman in an army office with fellow soldier

The problem is that my father cannot be replaced.

The whole Goodman family - from left, Margie, Susan, Louis, and Gary, wearing their best clothes. Probably taken around 1961.

Extra information may be sent or requested by emailing the site administrator.